The Two-Dimensional Structure of Musical Scales

Western music theory implicitly treats scales as one-dimensional objects — sequences of pitches ordered along a line. Yet the structure that gives rise to keys, modes, accidentals, and the circle of fifths is inherently two-dimensional: every note in a diatonic scale occupies a position on a two-dimensional integer lattice, and the scale itself is a path on that lattice. This structure exists independently of any assignment of frequencies — it is purely combinatorial.

This article develops the mathematics of this two-dimensional structure in two stages. Part I treats the lattice and its algebra: vectors, coprime bases, lattice-preserving transformations, the MOS (Moments of Symmetry) construction, and the interval system — all without reference to pitch or frequency. Part II introduces the tuning map, a linear function that assigns log-frequencies to lattice points, connecting the abstract structure to audible music. This clean separation reveals that structure and tuning are orthogonal: infinitely many tunings share the same tonal architecture.

1. Introduction: The Hidden Dimension

Consider the C major scale: C D E F G A B. In conventional music theory, this is a sequence of seven pitches ordered by frequency. Intervals are measured by counting steps along this sequence — a second spans one step, a third spans two, and so on. The entire framework of scales, keys, and intervals appears to live on a line.

But look more carefully. The step from C to D and the step from E to F are both "one step" in the scale, yet they differ in size. The major scale has five large steps and two small steps, arranged in the pattern L–L–s–L–L–L–s. This distinction between large and small is not a minor detail — it is the shadow of a second dimension.

The key insight: the diatonic scale is generated by repeatedly stacking a single interval — the generator (a fifth) — and folding the result within an equave (the octave). The chain of fifths F–C–G–D–A–E–B produces exactly the seven notes of the major scale. But this chain has its own geometry: each note has a position within the scale pattern and a position along the generator chain. These are two independent coordinates. The scale is not a line — it is a path on a two-dimensional lattice.

This article develops the mathematics of this lattice. Crucially, we separate the structure of the lattice (which is purely combinatorial — integers, vectors, paths) from the tuning (which assigns frequencies to lattice points). The structure comes first, because it is the structure that determines keys, modes, intervals, and accidentals. Tuning is a separate choice layered on top.

2. The Integer Lattice

The foundation is the two-dimensional integer lattice ℤ² — the set of all pairs of integers (a, b) with a, b ∈ ℤ.

The tonal lattice is the integer lattice ℤ², whose elements we call nodes. Each node v = (a, b) represents a potential pitch in the tonal system. At this stage, no frequencies are assigned — nodes are purely abstract positions.

Every structure we will define — scales, intervals, modes, accidentals — lives on this lattice as a combinatorial object. Frequencies enter only in Part II, when we define the tuning map.

3. Coprime Vectors and Bases

The lattice has a rich algebraic structure that governs how we can describe and navigate it.

A lattice vector v = (a, b) ∈ ℤ² is coprime (or primitive) if gcd(a, b) = 1. Equivalently, v is coprime if there is no lattice point strictly between the origin and v on the line segment connecting them.

Coprimality is a basis-independent property: if gcd(a, b) = 1 in the standard basis, it remains 1 in any other integer basis (because basis changes in ℤ² are given by matrices with determinant ±1, which preserve the gcd).

A basis for ℤ² is a pair of vectors {e1, e2} such that every lattice point can be written uniquely as n1e1 + n2e2 with n1, n2 ∈ ℤ.

Two vectors e1 = (a1, b1) and e2 = (a2, b2) form a basis of ℤ² if and only if:

That is, the matrix with columns e1, e2 has determinant ±1. In particular, both e1 and e2 must be coprime.

This means any two linearly independent coprime vectors whose coordinates satisfy the determinant condition form a valid basis — and every node in the lattice has unique integer coordinates in that basis. There are infinitely many such bases for ℤ², and the music-theoretic objects we define (scales, intervals, modes) take different but equivalent forms in each one.

In a 5L+2s diatonic MOS, the following are all valid bases for ℤ²:

- Standard basis: { (1,0), (0,1) }

- Step basis: { L, s } — where L and s are the large and small step vectors

- Generator–period basis: { vg, vp } — generator and period vectors

Each gives a different coordinate system for the same lattice. The choice of basis is a matter of convenience, not structure.

4. The MOS Construction

A Moment of Symmetry (MOS) scale is a specific combinatorial structure on the lattice, defined by a recursive process that produces two distinguished vectors and a scale path. The construction is purely structural — it takes a rational or irrational generator ratio as input and produces lattice vectors as output, with no reference to frequency.

Let γ ∈ (0, 1) be the generator ratio (the generator as a fraction of the equave). Starting from initial values:

At each step i = 0, 1, 2, …:

If Li < si: ai+1 = ai + bi, si+1 = si − Li, bi+1 = bi, Li+1 = Li

After d steps (the depth), the MOS scale has ad large steps and bd small steps, for a total of n = ad + bd notes per equave.

This is a variant of the Euclidean algorithm applied to the generator ratio. It simultaneously computes the step counts (a, b) and the residual step-size ratios (L, s) — but the latter serve only to determine which branch to take at each step. The structural output is the pair (ad, bd) and the path: the sequence of branch decisions (L > s or L < s) at each depth.

- Depth 0: (1, 1), L ≈ 0.583, s ≈ 0.417

- Depth 1: L > s → b = 2, (1, 2), L ≈ 0.167, s ≈ 0.417

- Depth 2: L < s → a = 3, (3, 2), L ≈ 0.167, s ≈ 0.250

- Depth 3: L < s → a = 5, (5, 2) = 5L + 2s = 7 notes

The path is (L>s, L<s, L<s) — encoded as the boolean sequence (false, true, true).

Every MOS scale at depth d ≥ 1 satisfies:

- Two step sizes: The scale has exactly two distinct step types, conventionally called L (large) and s (small).

- Maximal evenness: The L and s steps are distributed as evenly as possible within the equave.

- Myhill's property: Every generic interval (spanning k scale steps) comes in exactly two specific sizes — a minor and a Major variant — differing by one chroma c = L − s.

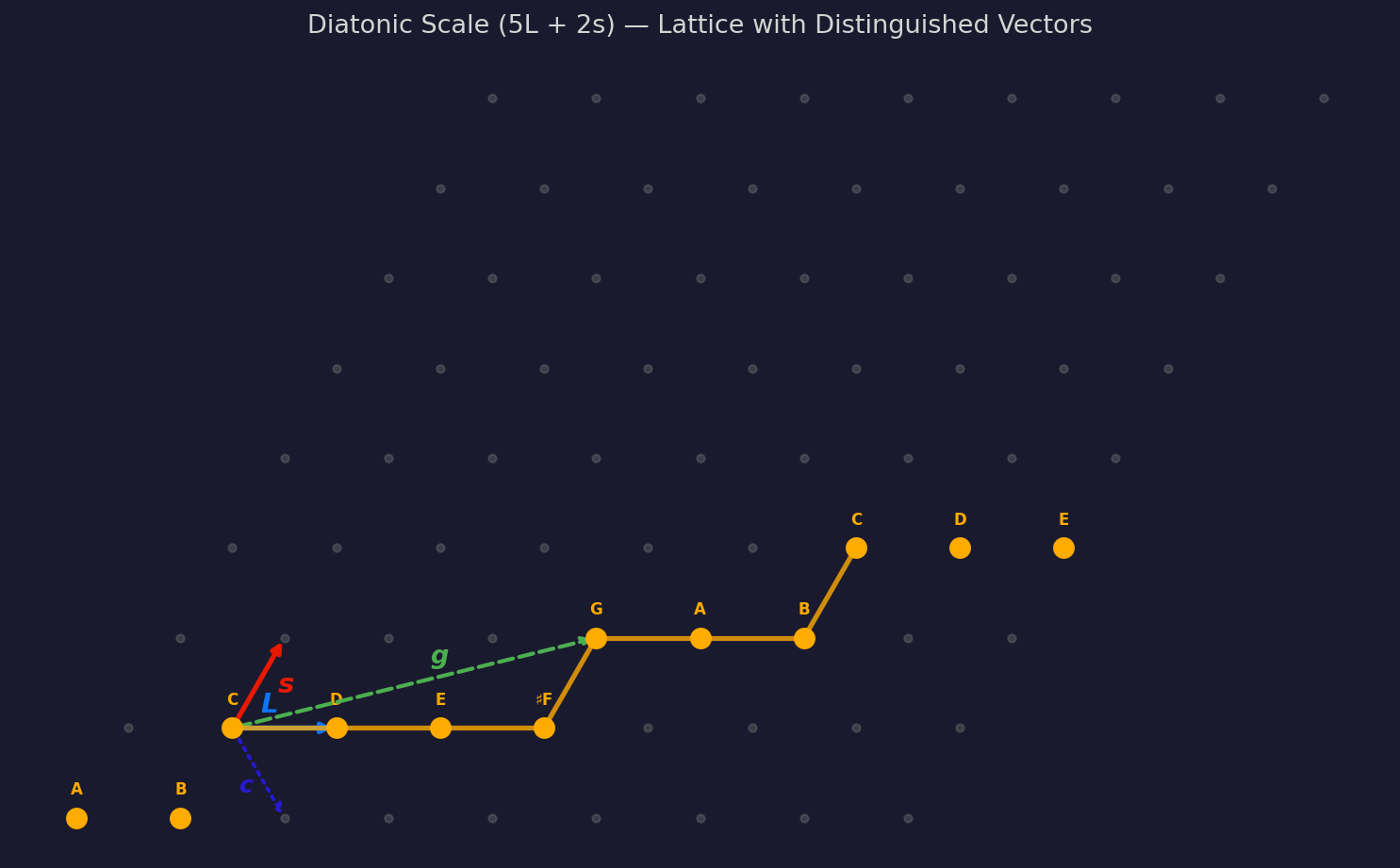

5. Distinguished Vectors

The MOS construction produces several important lattice vectors. These are elements of ℤ² — they carry no frequency information.

Given an MOS with a large and b small steps:

- Large step vector L and small step vector s: the two basis vectors corresponding to the two step types. These form a basis of ℤ² (since they arise from the Euclidean algorithm, their determinant is ±1).

- Period vector vp = a0 · L + b0 · s (where a0 = a/gcd(a,b), b0 = b/gcd(a,b)): represents one period of the scale in the lattice.

- Generator vector vg: the lattice vector reached by one generator step. Computed by applying the MOS path to the initial vector (1, 0).

- Chroma vector c = L − s: the difference between the two step vectors. In the diatonic case, this corresponds to a sharp/flat alteration.

Any pair of linearly independent vectors from this set forms a basis of ℤ². The {L, s} basis is natural for describing scales (steps are unit vectors). The {vg, vp} basis is natural for describing the generator chain (generators are unit steps). The choice is a matter of perspective, not structure.

6. Interval Structure

The two-dimensional lattice gives rise to a rich interval system that generalizes Western interval naming to arbitrary MOS scales.

A generic interval of an MOS scale is determined by the number of scale steps k it spans. By Myhill's property, each generic interval with 0 < k < n comes in exactly two specific sizes:

Major k-th (Mk): contains one more L-step (and one fewer s-step)

The difference between Mk and mk is always exactly one chroma c.

Our naming convention:

- P1 = unison (the zero vector)

- mk / Mk = minor / Major interval spanning k steps

- Pn = the equave (spanning all n steps = the period vector)

We deliberately avoid the traditional P4/P5 convention (perfect fourth/fifth), as it is specific to the diatonic scale and does not generalize. In a Porcupine[8] scale (1L + 7s), there is no structural reason to single out any interval as "perfect." Our notation treats all generic intervals uniformly.

| Steps | Minor | Major | Traditional Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | P1 (unison) | unison | |

| 1 | m1 | M1 | minor / major second |

| 2 | m2 | M2 | minor / major third |

| 3 | m3 | M3 | perfect fourth / tritone |

| 4 | m4 | M4 | tritone / perfect fifth |

| 5 | m5 | M5 | minor / major sixth |

| 6 | m6 | M6 | minor / major seventh |

| 7 | P7 (equave) | octave | |

Note that the traditional "perfect fourth" is our m3, and the "perfect fifth" is M4. The tritone at 600¢ in 12-TET appears as both M3 and m4 — it is the boundary where two generic intervals share a specific size. In non-equal temperaments, M3 ≠ m4: the tritone splits. This splitting is invisible in one-dimensional scale theory but natural in the lattice.

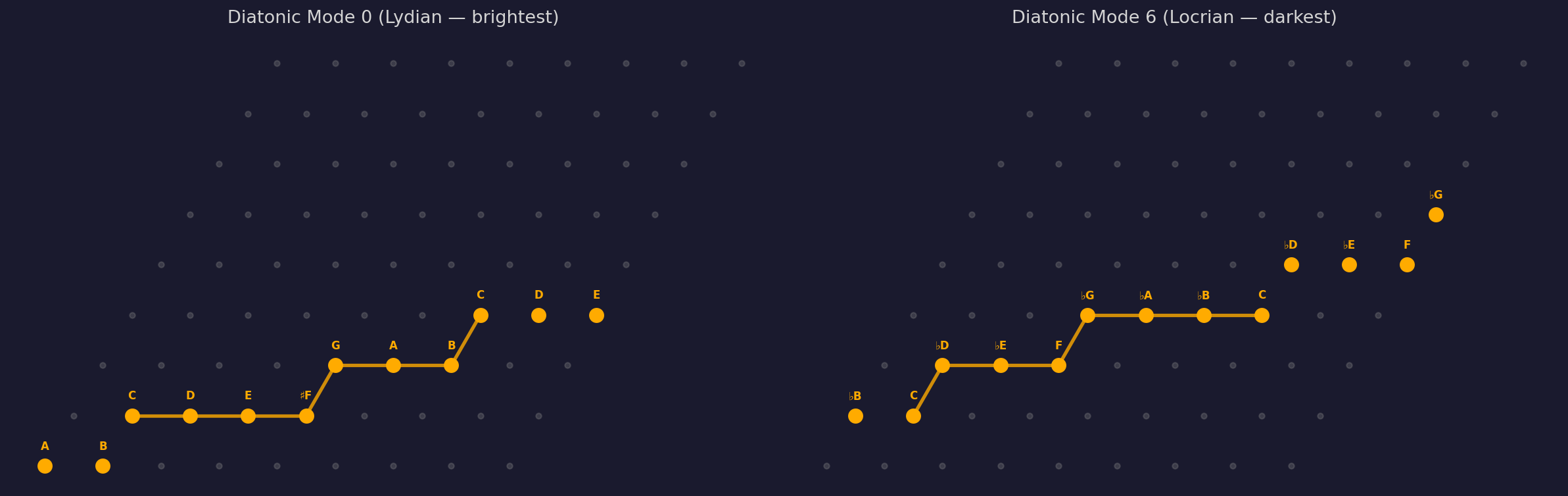

6.1 Interval Extraction from Modes

The complete interval set can be extracted by comparing two extreme modes of the scale. Mode 0 (brightest) and mode n−1 (darkest) represent the two extremes of the modal rotation. Comparing the lattice position of each scale degree between these modes gives all minor/Major pairs: the smaller value at each degree is the minor variant, the larger is the Major.

7. Modes and Accidentals

An MOS scale with n notes has n modes, corresponding to the n distinct rotations of its step pattern.

The mode m ∈ { 0, 1, …, n−1 } determines which rotation of the step pattern is used. Mode 0 has the brightest character (maximum large steps at the beginning); mode n−1 is the darkest. In diatonic terms: mode 0 ≈ Lydian, mode n−1 ≈ Locrian.

An accidental is a displacement of a scale note by one or more chroma vectors c = L − s. Adding a chroma raises a note by one "sharp" (♯); subtracting one lowers it by one "flat" (♭).

The accidental count of any lattice node is determined by its position relative to the scale: specifically, by its generator-chain coordinate modulo the scale size n0 (= n / gcd(a,b)).

Accidentals generalize perfectly to non-diatonic MOS scales. A Porcupine[8] scale has its own chroma vector with its own meaning — "sharp" and "flat" are structural operations on the lattice, not specific pitch adjustments.

8. Lattice Transformations and MOS Mapping

The set of invertible linear maps from ℤ² to itself forms the group GL(2, ℤ) — the group of 2×2 integer matrices with determinant ±1. These are precisely the basis changes of the lattice: each one maps every basis to another basis and preserves the lattice structure (every node maps to a unique node, and every node is hit).

A linear map M: ℤ² → ℤ² is a lattice automorphism (bijection preserving the integer lattice) if and only if M ∈ GL(2, ℤ), i.e., M is a 2×2 integer matrix with det(M) = ±1.

This has a powerful consequence for MOS scales: we can map between different MOS structures using GL(2, ℤ) transformations. Given two MOS scales with step bases {L1, s1} and {L2, s2}, the map that sends L1 → L2 and s1 → s2 is an element of GL(2, ℤ). This map establishes a structural correspondence between the two scale systems — every node in one lattice maps uniquely to a node in the other.

Crucially, this mapping operates purely at the structural level. It does not require that the tuning maps of the two systems are compatible. In particular, a vector that corresponds to a positive frequency interval in one MOS may correspond to a negative one in another — this is perfectly valid structurally, since the lattice itself carries no frequency information. The constraint that f(L) > 0 and f(s) > 0 belongs to the tuning, not to the structure.

9. The Tuning Map

So far, everything has been purely combinatorial — lattice vectors, scale paths, intervals, modes, and accidentals, all defined without reference to pitch or frequency. We now connect the lattice to audible music by introducing the tuning map.

A tuning map is a linear function f: ℤ² → ℝ that assigns a log-frequency (in cents, or equivalently log₂ of frequency ratio × 1200) to each lattice node. Linearity means:

A tuning map is uniquely determined by specifying f(e1) and f(e2) for any basis {e1, e2}.

The tuning map is what separates different tunings that share the same MOS structure. For a 5L+2s diatonic scale:

- Specifying f(L) = 200¢ and f(s) = 100¢ gives 12-TET

- Specifying f(L) = 203.91¢ and f(s) = 90.22¢ gives Pythagorean

- Specifying f(L) = 193.16¢ and f(s) = 117.11¢ gives quarter-comma meantone

All three produce the same scale structure — the same intervals, modes, accidentals, and lattice relationships. They differ only in the specific cent values assigned to each node. Structure and tuning are orthogonal.

Since the tuning map is linear and ℤ² has many bases, specifying f on any basis determines it everywhere. Common choices:

- Step basis: specify f(L) and f(s) — directly gives step sizes

- Generator–period basis: specify f(vg) and f(vp) — gives generator and period sizes. The generator ratio γ = f(vg) / f(vp) is PitchGrid's primary tuning parameter.

The tuning map also determines which of the two step types is "large" and which is "small" in pitch: we label them so that f(L) > f(s) > 0. This is a convention imposed by the tuning, not by the lattice structure itself.

10. Tuning Examples

10.1 Pythagorean Tuning (5L + 2s, g = 701.96¢)

The just fifth (ratio 3:2 = 701.96¢) produces the historical Pythagorean tuning. Under the tuning map: f(L) = 203.91¢ (Pythagorean whole tone), f(s) = 90.22¢ (Pythagorean limma), f(c) = 113.69¢ (Pythagorean apotome). Pythagorean tuning produces pure fifths but wide major thirds (407.82¢ vs. the just 386.31¢).

10.2 Quarter-Comma Meantone (5L + 2s, g = 696.58¢)

By narrowing the fifth by ¼ of the syntonic comma, meantone achieves pure major thirds (386.31¢) at the cost of slightly impure fifths. Same lattice structure as Pythagorean — same intervals, same modes, same accidentals — only the tuning map changes.

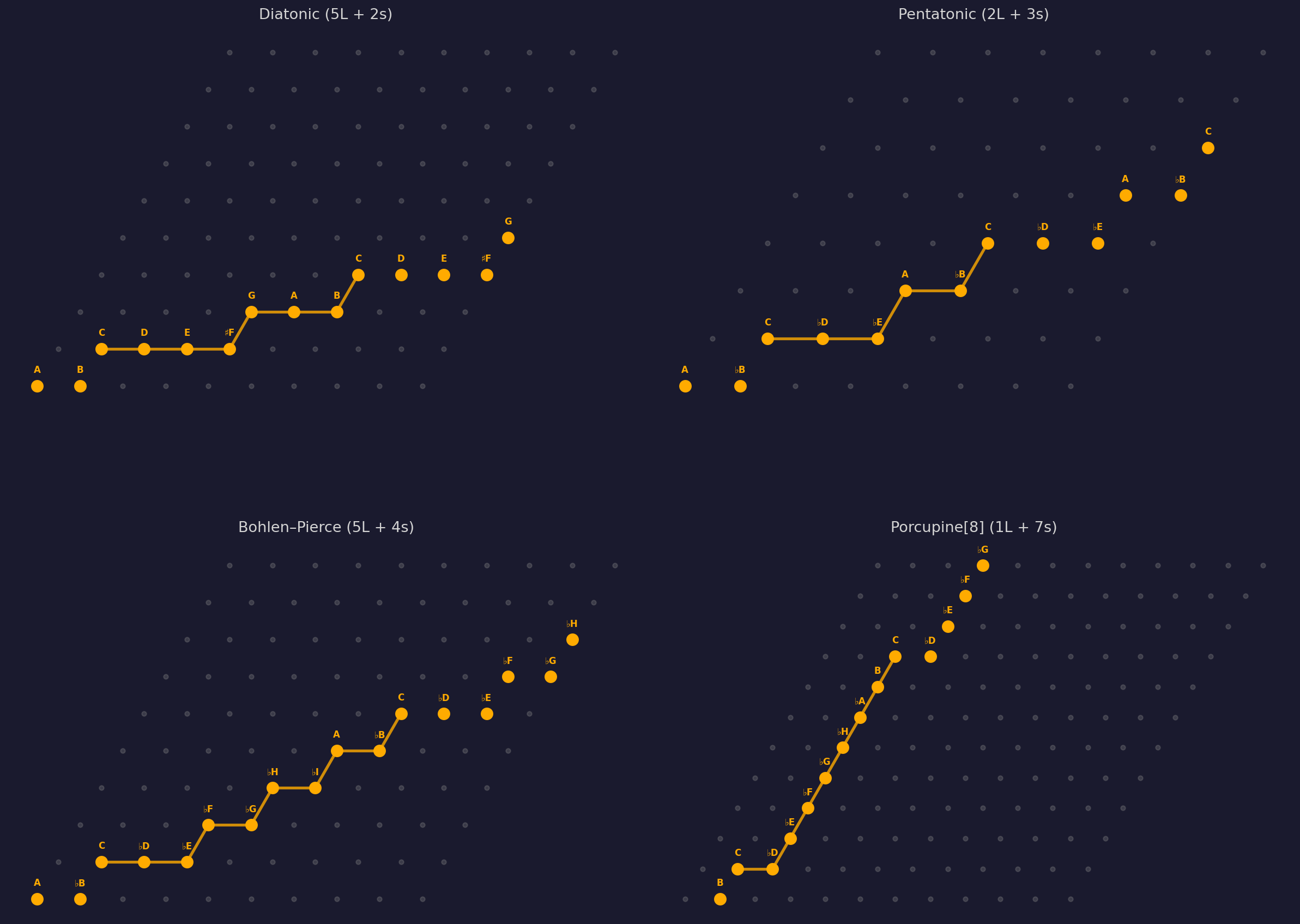

10.3 Bohlen–Pierce (5L + 4s, equave = tritave)

Bohlen–Pierce replaces the octave (2:1) with the tritave (3:1, ≈1902¢) as the equave. Its generator produces a 5L + 4s MOS at depth 4 — a 9-note scale within the tritave. The lattice structure is different from diatonic (5+4 vs. 5+2), giving it its own distinct interval system, modes, and accidentals. When paired with odd-harmonic timbres, it produces a convincingly consonant tonal system — as demonstrated in our consonance study.

10.4 Porcupine[8] (1L + 7s)

Porcupine temperament uses a generator near 163¢ (a neutral second). At depth 6, it produces 1 large step and 7 small steps — 8 notes per octave. The extreme asymmetry (1L vs 7s) produces a nearly equal-spaced scale with one "gap." Its consonance properties depend critically on timbre.

10.5 Slendric[11] (5L + 6s)

Slendric temperament produces an 11-note MOS with 5 large and 6 small steps. With nearly equal step sizes, it evokes Javanese slendro scales. The 11-note cardinality gives it a rich interval set with 35 distinct intervals up to 1950¢.

11. The Three-Gap Theorem

The MOS construction is intimately connected to the three-gap theorem (Steinhaus conjecture, proved by Sós 1958): when n points are placed on a circle at separations of an irrational fraction of the circumference, the gaps between consecutive points take at most three distinct values — and if there are three, one is the sum of the other two.

Let α ∈ (0, 1) be irrational and n ≥ 1. Place points at positions { k · α mod 1 : k = 0, …, n−1 } on the unit circle. The gaps between consecutive points take at most three distinct lengths. If exactly three lengths occur, one equals the sum of the other two.

MOS scales are precisely the case where exactly two gap lengths occur. This happens at cardinalities that are denominators of convergents or semiconvergents of the continued fraction expansion of γ. The depth parameter in PitchGrid indexes these special cardinalities.

Between two consecutive MOS cardinalities, the scale has three step sizes — these are the transitional "non-MOS" scales that PitchGrid traverses when depth varies continuously.

12. The Design Space and Open Questions

The rank-2 MOS framework reveals that the diatonic scale is one point in a vast design space of tonal structures, parameterized by:

- Generator ratio γ ∈ (0, 1): determines the MOS family. γ ≈ 7/12 gives diatonic; other values give Porcupine, Slendric, Mavila, and hundreds of other temperament families.

- Depth d ∈ ℕ: determines cardinality. For diatonic generators: depth 2 → pentatonic (5 notes), depth 3 → diatonic (7), depth 4 → chromatic (12).

- Equave: the interval of equivalence. Octave (2:1) is standard; tritave (3:1), or other values produce radically different tonal worlds.

- Mode m ∈ { 0, …, n−1 }: governs the bright/dark character of the scale.

- Tuning map f: assigns specific frequencies to the structure, independently of all the above.

Every point in this space defines a complete tonal system with its own intervals, modes, accidentals, and structural relationships — and for each structure, infinitely many tunings are possible. The consonance properties of each system depend on the interaction between the scale's intervals and the timbre's partial structure — as analyzed quantitatively in our spiky consonance study.

12.1 What Generalizes?

Western music has developed the most elaborate system of compositional devices in history: harmony, counterpoint, voice leading, chord progressions, cadences, modulation, and large-scale tonal architecture. All of these are built on the diatonic MOS structure. The central question is not merely what alternative scales sound like — it is which of these compositional devices generalize to the structurally analogous space of all MOS scales, and which are specific to the diatonic case.

Consider what changes when we move from 5L+2s to a different MOS:

- Chords are not stacks of thirds. In diatonic music, the triad (root–third–fifth) is a stack of two generic 2-step intervals. In a Porcupine[8] scale (1L+7s), the analogous structure would be a stack of 2-step intervals of a very different character. In Bohlen–Pierce (5L+4s), the basic harmonic unit spans different generic intervals entirely. The concept of building chords by stacking generic intervals generalizes; the specific stacking recipe does not.

- Chord progressions in Western music are governed by the circle of fifths — movement by the generator. Every MOS has its own generator, and therefore its own "circle." But the harmonic implications of moving by one generator step depend on the MOS structure: in a 5L+2s scale, moving by the generator changes one note by a chroma (key signature change); in other MOS scales, the same structural operation has a different effect on the scale content.

- Voice leading — the principle that voices should move by small intervals — is structural: it depends on the lattice geometry, not on specific frequencies. The smoothest voice leading between two chords depends on which lattice vectors are "small" — and this changes with the MOS structure.

- Counterpoint rules — constraints on simultaneous intervals and their progression — depend on which intervals are consonant and which are dissonant. In diatonic music, this classification is historically given. For arbitrary MOS scales, it can be derived from psychoacoustic analysis, enabling a principled generalization of counterpoint to any tonal structure.

- Resolution and tension — the sense that certain intervals "want" to resolve to others — arises from the interaction between consonance and voice leading. A dissonant interval adjacent to a consonant one on the lattice creates tension; movement to the consonant neighbor resolves it. This mechanism is structural and should generalize, but the specific patterns of tension and resolution will be different for each MOS.

12.2 Instruments and Interfaces

The standard piano keyboard is a physical encoding of the diatonic MOS structure: seven white keys (the natural notes of one mode) and five black keys (the chromatic alterations), arranged in the specific pattern of the 5L+2s scale. This layout is not structurally neutral — it privileges the diatonic scale and makes other MOS structures awkward to play.

Isomorphic controllers — instruments whose playing surface is a regular two-dimensional grid (such as the Lumatone, Linnstrument, or Dualo) — are naturally suited to the MOS framework. On an isomorphic layout, the same fingering pattern produces the same musical structure regardless of which MOS scale or tuning is selected. Transposition, mode changes, and even changes of MOS family become geometric operations on the grid, preserving the player's motor memory. The two-dimensional lattice that underlies MOS theory maps directly onto the two-dimensional playing surface.

12.3 Structure Survives Retuning

The separation of structure from tuning — the central theme of this article — has a striking musical consequence: the structural content of a composition can survive radical retuning. Consider a Bach fugue. Its architecture — the imitative entries, the voice leading, the formal structure — is determined by the lattice relationships between notes, not by their specific frequencies. Now retune the diatonic scale to a superpythagorean fifth of ~711¢ — a "7-limit diatonic" where the minor third shrinks to 7/6 (266.9¢ instead of the familiar ~300–316¢) and the major third stretches to nearly 9/7 (435.1¢). The harmonic color transforms completely: familiar intervals acquire an alien, septimal quality that evokes entirely different feelings from meantone or equal temperament. Yet the fugue still works — one still wants to listen to it. The entries fall on the right scale degrees, the imitation is intact, the formal architecture holds. On instruments with a strong 7th harmonic, these septimal intervals are surprisingly consonant, producing a distinctive sound that is unfamiliar but harmonically pleasing.

This is the power of the structure/tuning separation in action. The composition's meaning lives in the lattice — in the structural relationships between notes — not in their specific frequencies. Tuning determines color; structure determines architecture. They are orthogonal, and it is the architecture that carries the compositional content.

PitchGrid is a straightforward generalization of the Western tonal structure. The diatonic scale, with its modes, intervals, accidentals, and circle of fifths, is not an isolated phenomenon — it is one instance of a universal construction that produces infinitely many tonal systems with analogous structural richness. The mathematical framework is the same; only the parameters differ.

The question is not a binary "does it generalize or not" — we already know the answer is nuanced. Some features clearly generalize: the lattice structure, the interval system, modes, accidentals, and the basic mechanisms of voice leading and counterpoint have nothing inherently diatonic about them. Other features are specific: a chord progression like ii–V–I is a product of the 5L+2s structure, though it may have analogues in other systems that we have not yet discovered. The real question is: which compositional devices generalize, which transform into something new, and which are irreducibly diatonic?

Consider Bach. His music is not solely determined by harmonic laws — it derives much of its rich architecture from the symmetries that diatonic structure offers: the interplay of modes, the relationships between keys, the way voices can move independently while maintaining harmonic coherence. These are structural properties, not acoustic ones. When we leave the diatonic world, what PitchGrid reveals is that some of these symmetries break — but more importantly, the deeper structural features that give compositions their overall architecture are more general than the diatonic case. They carry over, in transformed form, to the entire MOS universe.

Western music spent centuries exploring the compositional possibilities of a single MOS structure (5L+2s) under a handful of tunings. The tools now exist — parametric scale construction, generalized notation, quantitative consonance analysis, isomorphic controllers, and software synthesis — to explore the rest of the space with comparable depth. Whether this perspective proves to be a fruitful ground on which music can further develop — offering structures as rich as those that enabled Bach, Beethoven, and beyond — is for composers and listeners to discover.

13. References

- Wilson, E. (1975). "Letter to Chalmers pertaining to Moments of Symmetry." Published at anaphoria.com.

- Carey, N. & Clampitt, D. (1989). "Aspects of Well-Formed Scales." Music Theory Spectrum, 11(2), 187–206.

- Clough, J. & Douthett, J. (1991). "Maximally Even Sets." Journal of Music Theory, 35(1/2), 93–173.

- Sós, V. T. (1958). "On the distribution mod 1 of the sequence nα." Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös Nominatae, Sectio Mathematica, 1, 127–134.

- Erlich, P. (1997). "Tuning, tonality, and twenty-two-tone temperament." Xenharmonikôn, 17.

- Milne, A. J., Sethares, W. A. & Plamondon, J. (2007). "Isomorphic controllers and dynamic tuning." Computer Music Journal, 31(4), 15–32.

- Bohlen, H. (1978). "13 Tonstufen in der Duodezime." Acustica, 39(2), 76–86.

- Sethares, W. A. (2005). Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale (2nd ed.). Springer.